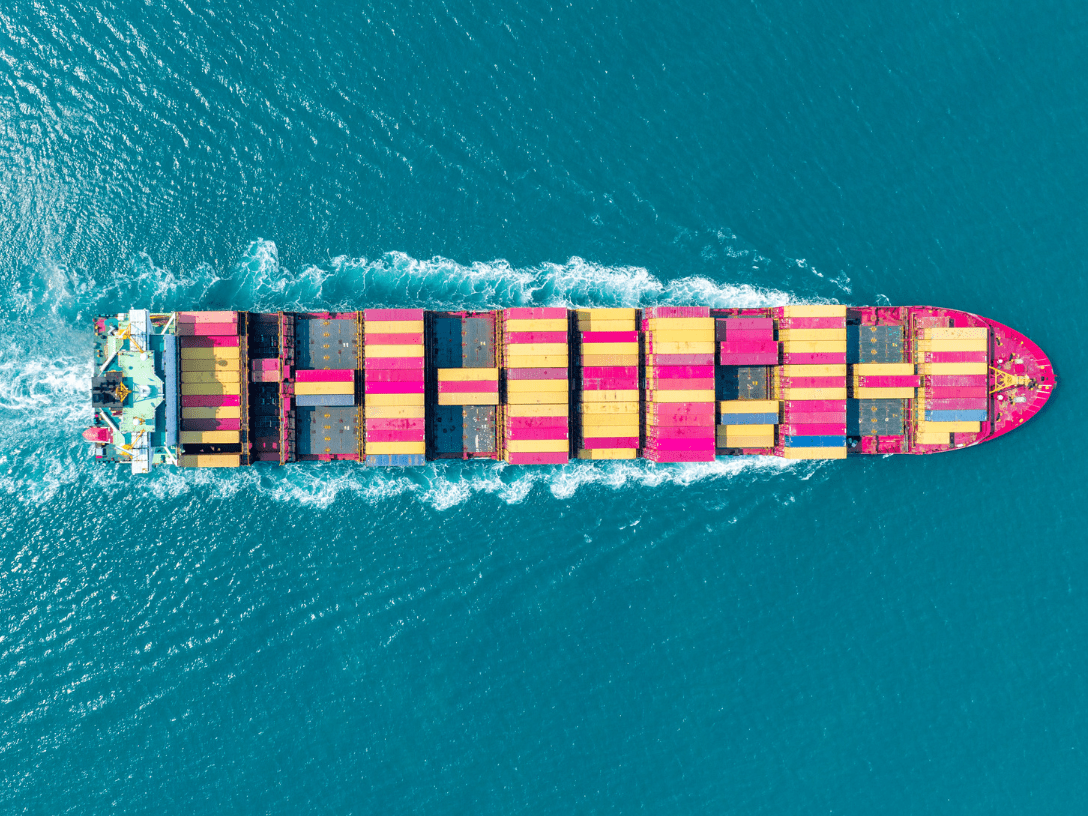

As the modern slavery bill travels through parliament, the spotlight has been turned on supply chain ethics and transparency – or lack thereof – within supply networks.

Home Office ministers claim that under the new legislation large businesses will need to disclose the steps they have taken to eradicate slavery from their supply chains each year. Britain’s first anti-slavery commissioner has also been appointed – in the form of Kevin Hyland, former head of London’s Metropolitan Police human trafficking unit – and he will be exposing companies that don’t put procedures in place to tackle slavery.

This will create a greater imperative to roll out supply chain visibility beyond the first tier for buying organisations.

“Once they know they are being monitored…they will want to have clean supply chains,” Kevin Hyland told the Financial Times. “If they fail, they will be exposed – and no company in the world wants to be shown as employing slaves.”

But what is the threat and what can businesses do to tackle it?

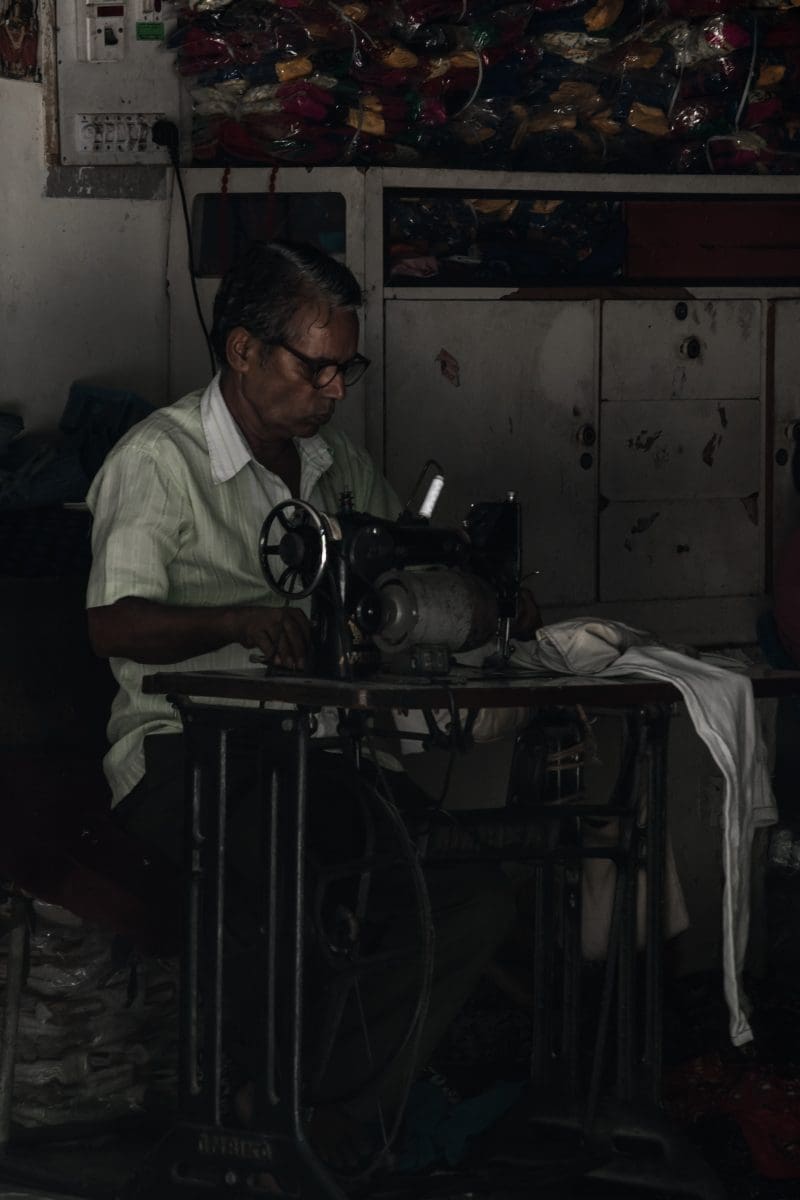

Unethical conduct in the supply chain

Slavery, forced labour and human trafficking are three of the main risks to supply chain ethics. Slavery refers to the treatment of another human being as if they were ‘property’ to be “bought, sold, traded or even destroyed”, according to the Walk Free Foundation. Forced labour is the taking of labour without consent through threats or coercion, while human trafficking is the purchase of individuals by deception, threat, or coercion into slavery, forced labour, or other forms of exploitation.

These actions violate human rights and are unfortunately more common than many believe. Indeed, the Walk Free Foundation claims there are 29.8 million people in modern day slavery, including 5,000 slaves in the UK.

The National Crime Agency has also identified that the number of potential victims of trafficking and forced labour in the UK rose by 47 per cent last year.

So why is this crime happening in the supply chain unbeknown to many? Research from Achilles has shown 40 per cent of businesses buying only in the UK have no information on second-tier suppliers and one in five organisations have no information about their tier-two suppliers across the world. Slavery is often buried deep in a supply chain and while the complex nature of networks makes it difficult to unearth, more can certainly be done to close the net around instances of abuse.

Currently, just 51 per cent of manufacturers regularly audit their tier one suppliers. There is a level of assumed trust with tier one suppliers but this may be preventing supply chains from being held to account.

Of concern is that Achilles found that just eight per cent of large manufacturers are “very confident” that their first tier suppliers do not use slave labour.

These figures have been backed up by the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply. In a study the body revealed that 11 per cent of business leaders have a supply chain they think is likely to contain modern slavery and 72 per cent of British supply chain professionals have zero visibility of their supply chain beyond the second tier.

Ensuring ethics in the supply chain

Protecting against unethical conduct in the supply chain boils down to one thing: transparency. While it’s not easy to shine a light on the deepest, darkest depths of the supply chain, with the right processes in place it is possible.

The first step is to ensure all suppliers complete corporate social responsibility questionnaires as part of pre-qualification. This means buyer organisations can identify points of weakness and take out any high-risk suppliers from the process.

As a member of Achilles, buyers can draw from a bank of validated suppliers and manage all supplier information through a single database.

Supply chain mapping is also an important tool for ensuring ethics run throughout supply networks. By sending automated requests for information through the supply chain, businesses can get a better understanding of what’s happening and where. However, it’s crucial to get the buy-in of first-tier suppliers, which can then help to identify sub-suppliers.

The final piece of the puzzle for ensuring supply chain ethics is auditing known suppliers. This is the physical validation of a company’s questionnaire. Achilles’ audits cover corporate social responsibility, health and safety, environment, carbon emissions, factory assessment, quality, business continuity and human resources.

Our audits reflect industry requirements, including standards, best practice and country-specific laws.

Preparing for an ethical future

With the UK cracking down on unethical supply chain conduct, organisations that can demonstrate transparency and give assurance that there are no instances of human rights abuses in their supply chains will pull ahead.

Getting ahead of legislation is important and companies will benefit from more ethical supply networks.

Speaking earlier this year, David Noble, group chief executive officer of the Chartered Institute of CIPS, said: “Consumers and business leaders have entered into a “don’t ask, don’t tell” pact on Britain’s supply chains. Neither consumers nor business leaders have learned the lessons of the horse meat scandal and are content to remain ignorant of the malpractice that could be operating throughout their supply chains.”

“If the modern slavery bill is to have a chance of eliminating slavery from British supply chain and we are to avoid repetition of the horse meat scandal, then we must empower procurement professionals within their businesses.”