Shipowners are clear-eyed people, nowhere more so than in Norway where the industry proudly trades on its heritage and longevity, with a keen focus on profitability. This longevity has come not by chance but through a focus on quality and sustainability. The country’s shipowners were some of the first to consider their impact on people and society as well as their balance sheet.

As a publicly-listed tanker operator, Odfjell has a long-standing commitment to environmental, social and governance matters and the balance between its impact on the planet and the profitability of the company.

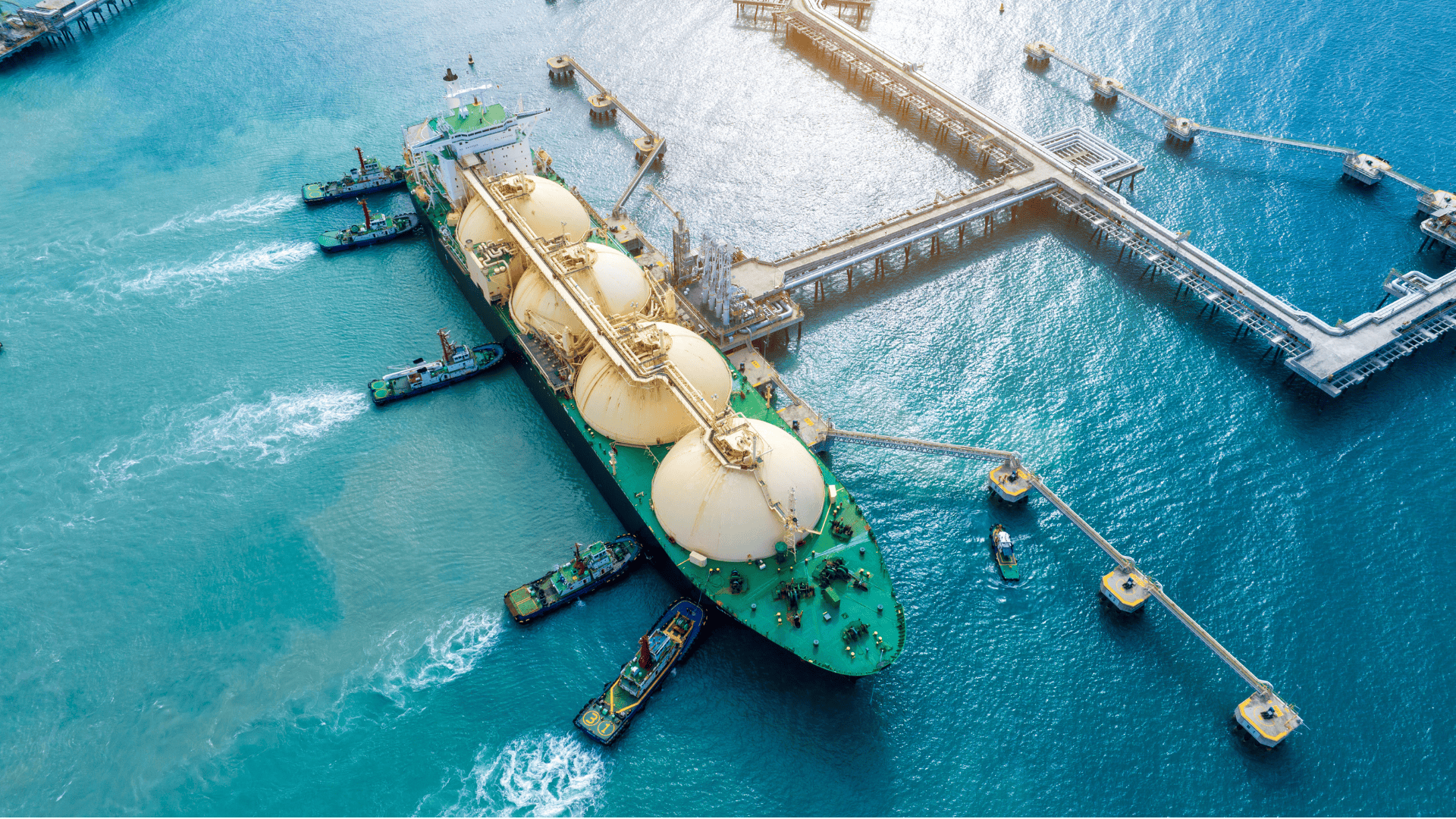

A global company with gross revenue of $1.194m in 2023, Odfjell employs more than 2,300 staff, operating a fleet of 70 vessels from 13 offices and four terminals at key strategic locations.

As Odfjell’s Chief Sustainability Officer Øistein Jensen explains, “We need to be profitable in order to be sustainable. These things go hand in hand. That means that we need to consider all our impacts on society and on people. I think that this has been a journey for most companies.”

The interest in ESG as a business tools is a natural development from the industry’s focus on safety and pollution from the 1970s onwards, which led in time to stronger internal controls and accounting practices.

“Now ESG matters have emerged and is something we must have on the agenda, We feel responsibility for our people, not only our own, but the people in the value chain as well,” he adds.

Jensen says Odfjell had previously collaborated with non-governmental rights organisations to investigate whether the workforce in its supply chain were treated in accordance with human rights regulations.

That led to further evaluation of platforms and systems that could fully monitor its supply chain. Jensen says it quickly became clear that not everything Odfjell was sourcing was done in a sustainable way and there was a risk of exposure to compromises of human rights.

“When we really started looking at developing a policy for human rights, a policy for sourcing, a policy for principles for suppliers, in order to make sure that we did not have any corruption in our supply chain and that we did not contribute to that,” he says.

The decision was accelerated by the development of Norway’s Transparency Act, a forerunner of the directives soon to enter into force across the European Union. The Act enshrined the responsible behaviour of companies into regulation and forced Odfjell to document the way it worked with its supply chain.

“We had the responsibility for our own business for a long time but now we needed to focus on upstream and downstream activities as well,” says Jensen. “It was an area where we did not have too much insight because we depended on the information that was given to us if we asked for it from suppliers.”

Being able to prove that it was compliant with transparency regulation and had a system in place to screen its suppliers on environmental, social and governance matters was initially the source of head-scratching. As Jensen points out, Odfjell is a big buyer, but by far from the biggest, so for some suppliers, it is just another company name on their list.

“Talking to other companies we found that buyers were all issuing questionnaires to their suppliers so the big suppliers were getting a lot of questionnaires going back and forth,” he adds. Odfjell even set up its own internal process before ultimately alighting on Achilles as a solution that shared and therefore reduced the scale of the problem.

“We developed the platform internally but the challenge was for the suppliers to put that data into the system. We saw that it was very complicated because when working with multiple suppliers because they found it cumbersome and challenging as well.”

Jensen’s previous experience with the platform in the oil and gas industries was enough to convince him that it could help solve the same problem of managing supplier screening and supply chain risk for Odfjell.

“What we wanted was a platform where we could have the benefit of a lot of shipowners together so that we could collaborate. When we started the dialogue with Achilles it was clear there was an opportunity because it already had a developed network,” he explains.

Among the practical benefits is the potential to plug the Achilles platform into Odfjell’s own systems such as its procurement portal so it can use the data directly in its day to day operations. Over time, it will become embedded in the way Odfjell does business.

Another is that the platform provides a transparent means of demonstrating compliance to its financial stakeholders, whose interest has also evolved from safety and environmental markers to include ESG metrics.

Odfjell had previously developed climate targets and linked carbon emissions to its financing to create a sustainability-linked framework to issue bonds and loans to investors.

“We were the first in the industry to do that, but when we met with a lot of investors, they asked us not only about emissions but also about people and about our supply chain,” he explains. “They wanted to make sure that we had a in policy and process in place across human rights, anti-corruption and sanctions.”

“The big driver and the big change now is that you cannot focus only on yourself. You need to take a bigger responsibility both upstream and downstream, and that is a big challenge because how do you screen hundreds of thousands of suppliers?”

The Achilles platform provides a unified means of demonstrating that such policies are in place and that Odfjell is compliant to OECD guidelines, EU regulation and Norway’s Transparency Act. Jensen says that means its relevance to the business can only grow.

“I think that, for us, Achilles will be an increasingly important tool for us to mitigate risk, drive our ambitions and help understand the impact of the business, wherever we are working, so we can demonstrate more sustainable performance.”